1. Identifying your Robin

Everyone knows what the Robin looks like; red breast, usually found on the front of Christmas cards, etc. But get up close to one, as I hope you will be able to with the lessons learnt here and you’ll discover how limited those preconceived ideas are. In fact, you’ll discover that really they’re orange breasted, not red.

The Robin is a very territorial creature, whose patch will cover up to a couple of acres. They don’t like sharing their space with other Robins and sometimes not even other small birds, such as Sparrows. I’ve seen a Robin dominate the bird feeder, chasing the other passerines off, as if it could eat the whole feeder full of seeds to itself, which we will see later is not possible.

They’re a fairly typical sized small bird, if you define the typical small bird as being “about Robin sized”. They weigh very little as you will find out for yourself later, around 25 grams, about the same as a tablespoon of flour (without the spoon). In size, they vary, even within the same Robin. They have the ability to puff themselves up when putting on a display, but also can change the shape of their head. Look at one straight on (in the beak) and sometimes the head will appear narrower, or pinched, at the level of the eyes. Other times the head can appear fatter and lower, more rounded and a little cuter. They stretch out, standing up and appear lean and more like a Sparrow in profile. Next they squat down rounding out into classic fat-Robin-on-a-Christmas-card pose. Then the wind catches their feathers, ruffling them up and showing the delicate shades of colour as the softer under feathers are back combed by the breeze.

2. Getting to know your Robin

Hopefully you’ll have already seen a Robin in your garden, using some of the information learnt from chapter 1. If not, try moving to another garden, or asking in your local pet shop if they’ve got any Robins under the counter. Getting a Robin mail order is frowned upon these days unfortunately.

With their inquisitive nature, they may already have followed you around the garden as you dig or weed, hopping over the newly exposed soil in search of grubs. Once familiar with you, you may even end up having to tell them to get out of the hole you are in the process of digging, which can then lead to the other classic Robin image; Robin-sat-on-handle-of-garden-spade.

The first step in getting the Robin to feed from your hand is to find out what he likes to eat. Whilst he will eat grain and seed, these can seem a little too wholesome and boring. I know we need five-a-day and all that but what will really get the Robin bouncing in anticipation is mealworms. These can be pretty pricey, and you can grow your own, but buying in bulk will make them a little cheaper and other birds like them too, such as Blackbirds who prefer to eat them off the lawn, rather than feeders, bird tables or hands. You can also use the mealworms to scare children by threatening to put some in their dinner.

The next step is to build your Transitional Feeding Station and reinforce this in the Robin’s mind. Whilst this technical sounding concept may be daunting, stick with me here. I use a wall that is about five feet tall. Whilst the height is important, the length and width are not so useful in the feeding of the Robin, but may have other uses in its secondary purpose of being a wall. Put some mealworms on top of the wall and wait. Now wait a bit more (this is the slightly important bit). Chase away the inevitable grey squirrel but feel free to allow any other birds to deplete your stock of mealworms.

After repeating this for a few days (you can go inside occasionally to get warm, but you will fear missing something), the Robin should be a regular visitor to the Transitional Feeding Station and be more comfortable in your presence. (If not, it might be wise not to wear a fox or bird of prey costume for this part.) He should now often appear nearby when you go into the garden and approach the TFS, maybe rewarding you with a little song. You are now ready to move to the next stage.

3. The next stage

This is where you really have to start working. The physical and mental effort required to get through the next stage will call upon reserves you didn’t know were there. It is not for the weak. Basically, to put it bluntly, and there’s no prevaricating around the bush here, it will hurt. You are going to be standing still, with your arm outstretched until your muscles scream.

The next time you go to the TFS, don’t put the mealworms on top. Put them in your hand, hold out your arm, stand a metre or two away from the feeding point and wait. You might want to do this when the Robin is there as well. This is where the height of the wall was so important; you want the Robin to be able to look down onto your hand. If the TFS (or wall) is too low, he won’t be able to see the mealworms and just think you look like you should have “Dorset 5 miles” painted on you.

Now feel the burn; you’re going to be holding this position for a long time. Your muscles will start to feel the heat, and all the while the Robin will stand there watching you. Hopefully he’ll start to turn his head sideways, looking side on down into your hand – they don’t look straight ahead in a general beakish direction, but with more of a twist.

After another hour, he might bounce down and back up once or twice. This is a good sign. Now you’re only a few more hours of muscle wrenching agony away from the next exciting small episode; the fly-past.

4. The next next stage

Now if you’re really patient s/he should be the approaching (but not crossing) of the bird-man threshold. After a quick bounce (and sometimes a small poo), the Robin will launch himself airborne, perform an awkward hover about six inches from your aching hand and then bugger off back to a perch.

Congratulations. This is an important achievement. You just have to repeat it over and over again. To be fair, the next stages progress rapidly. The second hover is followed by the first touch down. He won’t always take a mealworm at this stage, but we’re getting close. In my experience, he’s happier now he’s crossed the man-bird dividing line. Soon it will be the Taking Of The First Mealworm! He’ll unceremoniously grab it with no sign of gratitude and fly off, probably to the Transitional Feeding Station, a place he thinks of when he pictures you and a mealworm. The next time he may stay a while, gazing at the mealworms, before taking another and flying off. Soon he’ll sit a while longer and undertake his feeding in situ, on your palm.

5. Troubleshooting

Q1. Why won’t the Robin approach me?

A1. Are you sure it’s a Robin? Does he have the tell-tale orange breast? Is it roughly Robin sized? Make sure you’re not trying to feed the wrong bird, such as some sort of bird of prey.

Q2. He doesn’t like the food.

A2. Make sure you have mealworms. I’ve tried other foods such as toast, baked beans, caviar, spam but really mealworms are the three star meal of choice.

Q3. He’s just been sick!

A3. Yes, he does do that occasionally. Try not to take it personally, he’s just making room for more mealworms. (See also Q4.)

Q4. He’s just done a poo!

A4. Again, it’s perfectly natural. This is wildlife after all. Also might want to wear gloves while doing this. Maybe I should have mentioned this earlier. Sorry.

Q5. Where can I learn more?

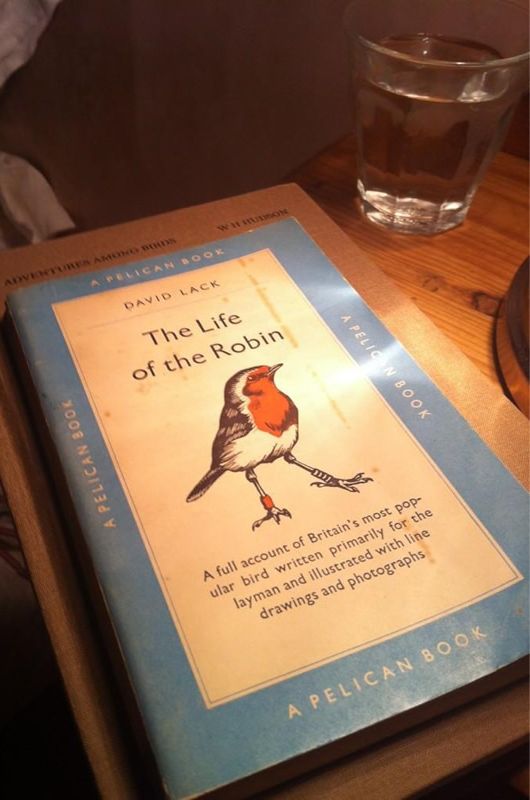

A5. Try and get a copy of “The Life of the Robin” by David Lack, published by Pelican (yes, really) back in 1943. You can find copies on Abebooks quite easily for a few quid. A more recent publication is “The Robin: A biography” by Steven Moss, which has some lovely drawings of eggs inside the covers.

6. Advanced Robin feeding

Congratulations, you have now been fully trained to feed a Robin. Who was training who here? Who was standing still, arm outstretched, holding a handful of worms and who was happily flying around, having a poo and singing to themselves? (I hope you were the former and the latter was the Robin.)

After a few days of this, you should start following each other around the garden. He’ll hop from branch to twig as you walk along wondering where he is, when he’s just beside you. Soon you’ll recognise his song (see below) and be able to spot him a garden or two away. The best moment of recognition I had was when he was more than three gardens away, atop a tree singing loudly to mark his patch, when we spied each other, smiled at each other, I held out my hand and he flew in drooping curves fifty metres or so, straight to my hand.

Soon he will be so familiar that he’ll come pestering you for food. Once I was sat in a chair, one ankle across the other knee, when he came and sat on my knee and berated me for not feeding him until I reached for the tub of mealworms I now always carry with me.

7. The songs

Basically he’s got two; the loud one sung in Spring when’s he on the pull, marking out you and your neighbour’s gardens as being his area and everyone better start buying mealworms right now.

The other song is a quiet, more Autumnal one, that he can quite often ventriloquise, making a series of soft notes and chirps without opening his beak. This is where the training is useful – you can get close enough to him to hear this song. Those who haven’t undertaken this training won’t ever be able to hear it.

8. The seasons

In late Spring, you should notice that he doesn’t always eat the mealworms there and then in your hand. He’ll gather up five or six at a time like some sort of bad Puffling impersonator and fly off. Congratulations! You are now a grandparent! He’s got a brood somewhere near by and he’s feeding them rather than himself. Keep up the work, those mealworms are needed more than ever now. He’ll look tired and bedraggled as will you as you start to worry about the little family nesting so close by but unseen. And then he’ll disappear.

Months will pass, you’ll walk forlornly around the garden, your pot of mealworms leaving a sour taste in your mouth. But wait! What’s that quiet Autumnal song? Who’s that shadowing your movements through the bushes!? Why, it’s your own little orange breasted stalker returning! Hold out your hand and with scarcely time for a small bounce, he’ll fly to your outstretched hand, those distant memories of your aching limbs once again forgotten.

And if you’re really lucky, you might even catch sight of a more hesitant second Robin, hopping from twig to stem a few metres away, wondering what the big thing his parent is sitting on is…

Postscript

I’ve included below links to even bigger pictures. These were taken with the camera lens about 4 inches from the Robin with a macro lens. Once he’s got used to you, you can get really close with the camera. I wanted to include the full size images as you can see every thread of his feathers.

Right click the links below and click “Open link in new tab” to see them full size. If you left click, they’ll pop in a smaller window.

robin_1.jpg (2.2MB, 2014 × 3039 pixels)

robin_2.jpg (2.2MB, 2014 × 3039 pixels)